...

Usability guru Jared Spool has written extensively about the ~“scent scent of information”information – how users hunt through a site, click by click, to find the content they’re looking for. Tree testing helps you us deliver a strong scent by improving organisation :

- organization (how

...

- we group

...

- headings and subheadings), and

...

- labeling (what

...

- we call each of them).

Anyone who’s watched a spy film knows that there are always false scents and red herrings to lead the hero astray. Anyone who’s run a few tree tests has probably seen the same thing – headings that lure participants to the wrong answer. We call these “evil attractors”“evil attractors”. These are headings that lure participants down the wrong path – not just for one task, but for several different tasks.

...

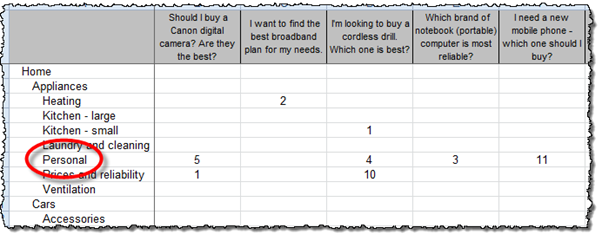

We ran the tests and got some useful answers, but we also noticed that there was one particular subheading (Home > Appliances > Personal) that got clicks from participants looking for very different things – mobile phones, vacuum cleaners, home-theatre theater systems, and so on:

The website intended this “personal appliance” category to be for products like electric shavers and curling irons, but apparently “Personal” meant many things to our participants, because they also went there for “personal” items like mobiles and cordless drills that actually lived somewhere else.

This is the false scent, the heading that “attracts” clicks when it shouldn’t, leading participants astray. Hence this definition:

| Notewarning |

|---|

| Evil attractor: A heading that draws unwanted traffic in several unrelated tasks. |

...

What makes an attractor “evil”?

Attracting clicks isn’t a bad thing in itself. After all, that’s what a good heading does – it attracts clicks for the content it contains (and discourages clicks for everything else).

“Evil” “Evil” attractors, on the other hand, attract clicks for things they shouldn’t. They “lure” users down the wrong path, at which point the user either find themselves in the wrong place, backs up, and tries elsewhere (if they’re patient), or gives up (if they’re not). Because these attractor topics are magnets for the user’s attention, they make it less likely that your our user will get to the place you we intended.

The other “evil” part of these attractors is the way they hide in the shadows. Most of the time, they don’t get the lion’s share of traffic for a given task; instead, they’ll siphon off 5-10% of the responses, luring away a fraction of users who might otherwise have found the right answer.

...

The easiest attractors to spot are those at the “answer” end of your our tree, where participants ended up for each task. If we can look across tasks for similar wrong answers, then we can see which of these might be evil attractors.

...

It’s usually not hard to figure out why an item in your our tree is an evil attractor. In almost all cases, it’s because the item is vague or ambiguous – something that could mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Look at our example above. In the context of a product-review site, “Personal” is too general to be a good heading. It could mean products you we wear, or carry, or use in the bathroom, or any number of things. So, when those participants come along clutching a task, and they see “Personal”, a few of them think “That looks like it might be what I’m looking for”, and they go that way.

Individually, those choices may be defensible, but as an information architectarchitects, are you we really going to group mobile phones with vacuum cleaners? The “personal” link between them is tenuous at best.

...

In the consumer-site example, we looked at the actual content under the “Personal” heading. It turned out to be items like shavers, curling irons, and hair dryers. A quick discussion yielded “Personal care” as a promising replacement – one that should keep away people looking for mobile phones and jewellery jewelery and the like.

In the second round of tree testing, among the other changes we made to the tree, we replaced “Personal” with “Personal care”. A few days later, the results confirmed our thinking – our former evil attractor was no longer luring participants away from the correct answers:

...

- Top-level headings are usually easy to check for evil attractors, if the tool you’re we’re using has a way of highlighting “first clicks”. If you we see a level-1 topic getting lots of incorrect clicks across several tasks, chances are that it’s an evil attractor.

A very common culprit is an “other stuff” heading like “Resources” Resources. It’s so general that it will get all kinds of traffic for all kinds of reasons. - Mid-level headings typically need a bit more detective work to see if they’re evil attractors. Usually this means eyeballing all your of our task results to see if certain mid-level topics are luring clicks when they shouldn’t. For more, see Where they went earlier in this chapter.

- ~need more on this

...

Next: Chapter 12 - key points

...