One of the most common ways of attracting participants is placing an “ad” on our website (and sometimes other websites as well).

The ad usually takes the form of an at-a-glance proposition (e.g. “Help us improve our site – win an Apple Watch!”).

Clicking the ad can either take the user directly to the tree test (where the study is briefly explained) or to a page on our website that explains the research and links to the tree test from there.

Choosing websites for the ad

If we’re running a tree test to improve our own website, then that’s the obvious place to run the ad, because we’re automatically getting the right users.

If our website gets a lot of traffic, then the small percentage of visitors who click through to the study may provide the numbers we need to confidently analyze the results.

If our website doesn’t get enough traffic on its own, or if it’s a new website that we’re creating, then we’ll need to find other websites that:

- Attract the type of users who would conceivably use our website too, and

- Are willing to put our ad on their pages (for free, for money, or for some other arrangement we can make with them).

For example, we ran a tree test for a New Zealand government agency using web ads. Their own site didn’t get much traffic, so they contacted colleagues who ran other government sites and asked for help. Eventually their ad ran on half a dozen Ministry and department websites and they got a very healthy number of participants. (And they returned the favor later when those other sites ran their own online studies.)

If we do place web ads on sites other than our own, we should be sure that our ad and our explanation (discussed below) are clear about what they’re testing. For example, if we’re testing site A, and we place an ad for it on site B, make sure the ad is clearly for site A. Otherwise we run the risk of:

- Attracting users who may not be who we want

- Confusing or unintentionally misleading users who then abandon the study.

Where to place the ad

The global header is usually the best (and often the easiest) place to put a web ad.

- It appears on every page of the site, so every website visitor has a chance of seeing it.

- Adding a “banner” ad across the top of a page is usually easier to do than trying to insert it into the various page layouts that the site uses.

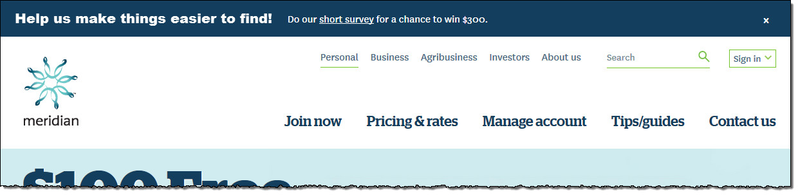

- Many sites already have an “announcement” banner feature that we can use for the ad. We just provide the text and the destination link:

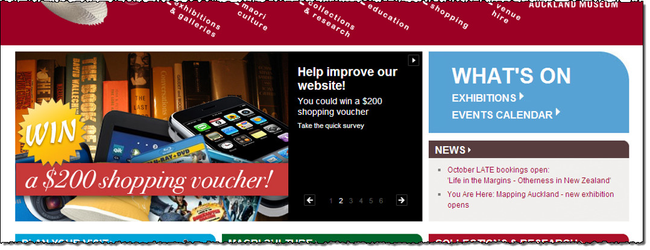

The home page is another popular spot for a web ad, because it usually already has a "feature" area or carousel that we can use:

The problem with home-page ads, however, is that many visitors never see the home page because they jump directly into the depths of a site from a search engine.

If the site has a library of ads that it serves up on various pages, we can also get ours added to the mix. In this case, we just need to create an ad with the proper dimensions, graphic format, and so on.

If we’re looking for specific types of users, we may want to run the ad on corresponding pages of the site. In the Shimano example we saw earlier (where they split their website into sections for cyclist, rowers, and anglers), if we were targeting cyclists, then we would obviously advertise our study on the cyclist pages of the site (and perhaps the general pages too), but not on the rowing or fishing pages.

We may also want to use pop-up ads, also known as "intercept" ads. These are often triggered when a user has been on a page for a certain period of time, when they scroll up, or when they try to leave the page. The more obnoxious variety appear in the middle of the screen, blocking the user's view of the content, and we don't recommend them. The more polite variety pops up in a corner of the screen (often the lower right), and tries not to get in the user's way.

Creating an ad

There are countless books and articles on how to create effective ads. For our online study, though, we really just need to focus on two factors:

- Attracting attention to the ad

- Conveying the proposition at a glance

To attract attention:

- Make sure the ad appears in a spot that website visitors are likely to see.

Generally this means anything at the top of the page, especially the top center. - Use colors or graphics that draw the visitor’s eye.

For example, when we do banner ads across the top of website pages, we usually pick a saturated color that stands out from the other content.

We can also use an image to create visual interest. If we’re doing a prize draw (a common incentive), we’ll sometimes use an image of the prize (e.g. an iPad).

Once we have a visitor’s attention, we have a few seconds (at most) to convince them to participate. Like a roadside billboard, we are usually limited to the small amount of text that a “passer-by” is willing to skim.

We typically phrase the text as a simple value proposition: Do this, and we’ll give you that. Here are some examples:

Do our 5-minute survey, get in the draw for a tablet!

Help us make things easier to find - win an Apple Watch!

We also need to make it clear what they should do next, if they decide to participate. This can be a clear text link (colored/underlined text) or a separate button.

But it's not a survey, is it?

Wondering why we keep calling our study a "survey" in the examples above? To be sure, a tree test is not a survey; at least, it's not the traditional questionnaire that most people call a "survey".

The problem with using the term "tree test" is that most people don't know what a tree test is. When presented with an unknown like this, many people will turn it down just because it's something new that they aren't interested in learning about.

By calling our study a "survey", we are offering them something familiar, which is easier to say yes to. Once they click to the tree test, they'll find it's a bit different from a traditional survey, but most will proceed as long as it looks reasonably brief and easy to do.

Creating an explanation page

Before participants actually do our test, we’ll need to give them a bit of preamble, typically including items such as:

- What the study is for

- How long it will take

- What their reward is

- What we will do with the results

- Any other “fine print” that we need to include (such as terms and condition of the prize draw, if we’re doing one)

We may want to cover this in the test itself (for example, on the welcome page), or we can put it all on an explanation page on our website. We typically do the latter, because many of our clients already do it this way for other online studies they conduct (such as user surveys).

While we do need to cover the items mentioned above (and perhaps other points specific to our research), we also need to do this briefly and concisely, and give them an obvious way to start the study. Otherwise, we’ll see a fair number of people dropping out because this is all taking too long or looking a bit complicated.

Here’s a typical explanation page that covers the basics and provides a clear way to start the study:

(Feel free to download and customize this example as needed.)

This content will probably be similar to what we put in our email invitations (if we’re also recruiting by email) – see Using email lists later in this chapter.

Next: Using email lists

Add Comment